Digital platforms - what are they and how can we rein them in

Note: this has been written as a submission for the "Rethinking Capitalism" module that I've taken as part of the MPA programme at UCL IIPP.

Introduction

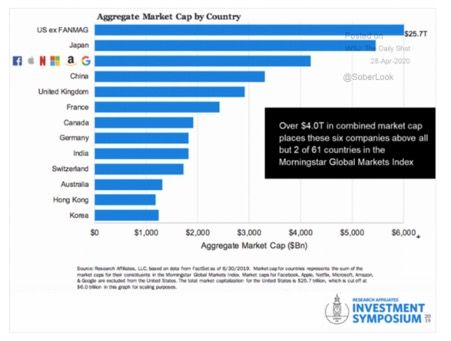

Digital platforms (henceforth DPs) have become the dominating companies of the past two decades. They have largely transformed the way we live, all the while becoming some of the most valuable companies in the world (the market capitalisation of the 6 largest tech companies is larger than any national stock market capitalisation other than Japans’ and the US excluding them. (see Figure 1)), while at the same time holding a fraction of the physical capital and employees of many of their competitors in other sectors, relying more on intangible goods, most predominantly data (Haskel and Westlake, 2018).

In this paper, I will first describe the main characteristics of DPs. I will then present the main problems they create for economies, followed by a number of potential solutions proposed in the literature. I will conclude by arguing that the underlying reason for the problems these companies cause is a mentality of unbridled growth that needs to be challenged.

Characteristics of data platforms

The most common characteristic of DPs is their business models’ reliance on collecting, processing and analysis of data generated by the platforms’ users. Coupled with machine learning algorithms, this practice is also known as big data.

Indeed, data has been compared to oil as the raw resource of the new economy (“Data is giving rise to a new economy,” 2017). What’s striking about this is that most companies obtain that data for free, or as a by-product of economic or everyday activity, what has been dubbed “data exhaust” (Zuboff, 2015) or “behavioural surplus” (Zuboff, 2019). Some of these platforms, e.g. Facebook and Google, have managed to extend their data collection outside their platform, tracking user activity on the entire web (Wagner, 2018). The constant collection and analysis of data leads to continuous improvements, experimentation and optimisation (Zuboff, 2015).

How these platforms monetise that data differs, just as oil can be transformed into petrol, plastic, kerosene. Google and Facebook predominantly use their users’ data to serve them targeted ads, while keeping their services free for consumers, thus ensuring more users – and more data. In 2018, the two companies had a market share of 60% of the digital advertising market in the US, which surpassed TV & print advertising the same year (Wagner, 2019).

These same platforms also rely on user-generated or uploaded copyrighted content or aggregating existing content from the Internet (like search engines do) to maintain user attention and arguing that they are doing a public service because “information wants to be free” (Levine, 2011). Coupled with an almost zero marginal cost of serving the same content to billions of users, this creates never-before seen economies of scale.

Other platforms’ business models rely on being market-makers (sometimes coupled with the “gig economy” – allowing users to use their existing assets like cars or homes and free time to earn money in a flexible manner). For example, Uber is an intermediary between drivers and customers, all the while doing regulation arbitrage.

A platforms’ success depends on whether they can leverage the network effect (Foroohar, 2019, pp. 20–23). This means that the more users a platform has, the more it is bound to attract. This creates incentives for companies to prioritise userbase growth rather than revenue in the first stage of business development.

Problems & Challenges

Each of the characteristics presented above creates their own set of problems. As seen above, DP companies require leveraging the network effect to increase their user base (and the amount of data they can mine off of their users). Network effects create great premises for natural monopolies (Foroohar, 2019, pp. 20–23). A natural monopoly is predicated by high barriers to entry in a specific industry.

However, current antitrust policies in the United States (where a lot of the DPs are headquartered) are geared towards consumer welfare, generally defined by short-term price changes, as opposed to the structure-conduct-performance paradigm (Khan, 2017). We have seen above that, generally speaking, platforms rarely raise costs directly to consumers, prioritising acquiring as many users as possible to profits, or even giving their products away for free, buoyed by venture capital. This leads to platforms flying under the radar of anti-trust regulators, all the while acquiring even more market power. Facebook’s acquisition of rivals Instagram and WhatsApp were agreed without a big challenge from antitrust regulators, whilst Amazon has been using predatory pricing to drive competitors out of business or acquire them (Khan, 2017).

A problem related to predatory pricing is the possibility of personalized pricing (Khan, 2017). The practice would allow companies to charge the maximum amount that they think a customer is willing to pay. Considering the amount of data DPs have available on their customers, this practice could lead to extremely efficient profiling and targeting on their part, maximising their profits, and making consumer welfare-based antitrust enforcement even more problematic.

Another problem raised by some DPs is that they “both operate a platform and market their own goods on it”(Khan, 2019). Amazon is both a market where vendors can sell their wares, but it is also selling its own line of essential products, plus their own e-reader devices and tablets, while Google is a search engine but also has many other services, which it prioritises against its competitors in their search results. This creates perverse incentives for these companies and leads to anticompetitive practices.

Platforms can collect large swathes of data because of the inherit informational asymmetry between end users and the platforms. Firstly, it would take a considerable effort to actually know ones’ contractual rights with each platform that a person interacts with. A paper (McDonald and Cranor, 2008) has calculated that reading all the online privacy policies that a person encounters in one year would take 76 working days. Secondly, the problems around informational asymmetry are compounded by the black-box algorithms used by these companies and the difficulty in exposing the biases that these algorithms display. Complex machine-learning algorithms hide their inner workings even from the programmers that originally wrote and trained them (Barton, 2019; Knight, 2019).

Platforms are also a threat to the labour market. Uber has long been accused of treating its’ drivers unfairly by not considering them employees and not offering benefits like sick pay, or allowing them to set their own rates, though this has been challenged in the UK. (Browne, 2018). Amazon has come under scrutiny for continuously monitoring their warehouse workers (gathering evermore data) and for repeatedly stopping their workers’ attempts at unionising (Lecher, 2019; Sainato, 2019).

At the same time, both Uber and Google have been trying to make drivers redundant, by creating self-driving cars. Google is creating even stronger cross-sectoral synergies by using their users’ input from around the internet trying to log in to different websites to train their cars (Healy, 2018).

Possible solutions

There have been a lot of suggestions or initiatives on how to tackle the undue influence of DPs. Paul Romer has suggested levying a tax on “revenue from sales of targeted digital ads” (Romer, 2019). This would reduce the profitability of the business model favoured by many platforms, and thus provide incentives to create new business models which would not imply invasive data collection. There is merit to this idea. Apple’s business model does not involve ads but selling devices and creating markets for third-party apps on those devices. Their data practices are markedly better than Facebooks’ or Googles’.

There are other ideas around taxation, such as Joseph Stiglitz’s proposal for a global flat tax rate on DPs set up to avoid their race to the bottom enabled by their reliance on intangibles (Foroohar, 2019, p. 280). California has proposed a “digital dividend”, in which all citizens that use the Internet would receive a fee, paid from data extractive DPs’ revenues (Foroohar, 2019, p. 276). Finally, Bill Gates has proposed taxing labour done by robots as a way of increasing revenue for education for reskilling those losing their job to automatization (Delaney, 2017).

Others favour the idea of enforcing interoperability and shared protocols (Masnick, 2019). In practice, this would mean that e.g. Facebook would share a protocol so that other social networks could share content to it, and it could share content to them, similar to how email or the telephone network works. This would address the high costs of switching social networks, thus reducing the barriers to entry, and allow different business models to flourish. Recently, Twitter has announced that it is researching such an open protocol for a decentralised social network (Robertson, 2019). There are limits to this approach. Email is a decentralised system, but the US consumer email market is still largely dominated by Outlook, Yahoo Mail and Gmail (“The Most Popular Email Providers in the U.S.A.,” n.d.). There have also been forceful calls to break up big tech companies, most famously by U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren (Warren, 2019).

Another suggestion is setting up data trusts, which would act like unions on the behalf of users whose data is being extracted and used by DPs (Hardinges, 2018). These would provide stewardship, and would allow better negotiation positions for users, and help mitigate the aforementioned information asymmetry. A pilot similar to a data trust, implemented in Barcelona and backed by the EU, aims at creating a “data commons” by allowing users to share personal data on their own terms (“What is DECODE?,” 2017). It also requires companies to put data they collect in Barcelona into public trusts, so that they can be reused by competitors, researchers or citizens. This would make data less like oil, and more like sunlight, non-exclusionary and usable by all (“Are data more like oil or sunlight?,” 2020).

There have also been calls to create an international organisation akin to the World Trade Organisation that would create global standards for extracting and handling user data, intellectual property and transferring them between jurisdictions (Bremmer, 2019). Both this and the aforementioned idea for a global digital flat tax rate show that the challenges that these platforms pose are global in nature, and their solutions have to be the same.

Conclusion

We have seen above that DPs create immense value for their shareholders, while obtaining their raw data for free, using less capital, and employing fewer people than traditional businesses, while actively destroying jobs through automatization. It is no wonder then that these companies are being accused of increasing inequality. But it does not have to be this way.

As Rushkoff argues (Rushkoff, 2016), these platforms behave in an accumulative and extractive matter because they are mimicking and exacerbating the mass-production socio-technological paradigm (Perez, 2004) in which they were born, instead of leaning fully into the possibilities of the internet age. They are led by shareholder-value doctrine, maximising profits and growth at all costs, and have turbocharged these by their network effects, infinitesimal marginal costs and the massive scale afforded by the internet.

But the Internets’ promise was of a peer-to-peer economy, of small websites and creators in federations, not of monolithic conglomerates dominating everything. And we are seeing the seeds of this promise of the internet in phenomena like crowdfunding, allowing collective decisions on where value might lie on a scale not encountered before, through websites like Kickstarter and Patreon. We also see it in more ethical platforms, like Bandcamp or Etsy, which allow their creators to name the terms of how they want to sell their content or artisanal wares, or in aforementioned projects like Decode which give users control of their data, and in federated social networks like Mastodon. The internet can still show us the way to a distributed, collaborative and innovative economy, but it requires changes like the ones outlined above, and more fundamental changes to our capitalist system, aimed towards stakeholder-value, more patient capital and with less emphasis on growth.

Bibliography

click to expand

- Are data more like oil or sunlight?, 2020. . The Economist.

- Barton, N.T.-L., Paul Resnick, and Genie, 2019. Algorithmic bias detection and mitigation: Best practices and policies to reduce consumer harms. Brookings. URL https://www.brookings.edu/research/algorithmic-bias-detection-and-mitigation-best-practices-and-policies-to-reduce-consumer-harms/ (accessed 4.28.20).

- Bremmer, I., 2019. Why we need a World Data Organization. Now. [WWW Document]. GZERO Media. URL https://www.gzeromedia.com/why-we-need-a-world-data-organization-now (accessed 4.26.20).

- Browne, R., 2018. Uber loses appeal against landmark UK workers’ rights ruling [WWW Document]. CNBC. URL https://www.cnbc.com/2018/10/31/uber-loses-appeal-against-landmark-uk-workers-rights-ruling.html (accessed 4.29.20).

- Data is giving rise to a new economy, 2017. . The Economist.

- Delaney, K.J., 2017. Bill Gates: the robot that takes your job should pay taxes — Quartz [WWW Document]. URL https://qz.com/911968/bill-gates-the-robot-that-takes-your-job-should-pay-taxes/ (accessed 4.29.20).

- Foroohar, R., 2019. Don’t be evil: the case against big tech.

- Hardinges, J., 2018. What is a data trust? – The ODI. URL https://theodi.org/article/what-is-a-data-trust/ (accessed 4.27.20).

- Haskel, J., Westlake, S., 2018. Capitalism without capital: the rise of the intangible economy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

- Healy, M., 2018. Is reCaptcha Training Robocars? Ceros Originals. URL https://www.ceros.com/originals/recaptcha-waymo-future-of-self-driving-cars/ (accessed 4.29.20).

- Khan, L., 2019. The Separation of Platforms and Commerce (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 3180174). Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY.

- Khan, L.M., 2017. Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox [WWW Document]. URL https://www.yalelawjournal.org/note/amazons-antitrust-paradox (accessed 4.20.20).

- Knight, W., 2019. The Apple Card Didn’t “See” Gender—and That’s the Problem. Wired.

- Lecher, C., 2019. How Amazon automatically tracks and fires warehouse workers for ‘productivity’ [WWW Document]. The Verge. URL https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/25/18516004/amazon-warehouse-fulfillment-centers-productivity-firing-terminations (accessed 4.29.20).

- Levine, R., 2011. Free ride: how digital parasites are destroying the culture business, and how the culture business can fight back, 1st ed. ed. Doubleday, New York.

- Masnick, M., 2019. Protocols, Not Platforms: A Technological Approach to Free Speech [WWW Document]. URL https://knightcolumbia.org/content/protocols-not-platforms-a-technological-approach-to-free-speech (accessed 4.27.20).

- McDonald, A.M., Cranor, L.F., 2008. The Cost of Reading Privacy Policies.

- Perez, C., 2004. Finance and technical change: a neo-Schumpeterian perspective (Working Paper). CFAP, Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge. http://www.dspace.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/225169

- Robertson, A., 2019. Twitter is funding research into a decentralized version of its platform [WWW Document]. The Verge. URL https://www.theverge.com/2019/12/11/21010856/twitter-jack-dorsey-bluesky-decentralized-social-network-research-moderation(accessed 4.27.20).

- Romer, P., 2019. Opinion | A Tax That Could Fix Big Tech. The New York Times.

- Rushkoff, D., 2016. Throwing rocks at the Google bus: how growth became the enemy of prosperity. Portfolio/Penguin, New York, NY.

- Sainato, M., 2019. “We are not robots”: Amazon warehouse employees push to unionize. The Guardian.

- The Most Popular Email Providers in the U.S.A. [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://blog.shuttlecloud.com/the-most-popular-email-providers-in-the-u-s-a/ (accessed 4.29.20).

- Wagner, K., 2019. Digital advertising in the US is finally bigger than print and television [WWW Document]. Vox. URL https://www.vox.com/2019/2/20/18232433/digital-advertising-facebook-google-growth-tv-print-emarketer-2019 (accessed 4.28.20).

- Wagner, K., 2018. This is how Facebook collects data on you even if you don’t have an account [WWW Document]. Vox. URL https://www.vox.com/2018/4/20/17254312/facebook-shadow-profiles-data-collection-non-users-mark-zuckerberg (accessed 4.27.20).

- Warren, E., 2019. Here’s how we can break up Big Tech [WWW Document]. Medium. URL https://medium.com/@teamwarren/heres-how-we-can-break-up-big-tech-9ad9e0da324c (accessed 5.4.20).

- What is DECODE? [WWW Document], 2017. . DECODE. URL https://www.decodeproject.eu/what-decode (accessed 4.28.20).

- Zuboff, S., 2019. Surveillance Capitalism and the Challenge of Collective Action. New Labor Forum 28, 10–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1095796018819461

- Zuboff, S., 2015. Big other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization. Journal of Information Technology; London 30, 75–89. http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/10.1057/jit.2015.5